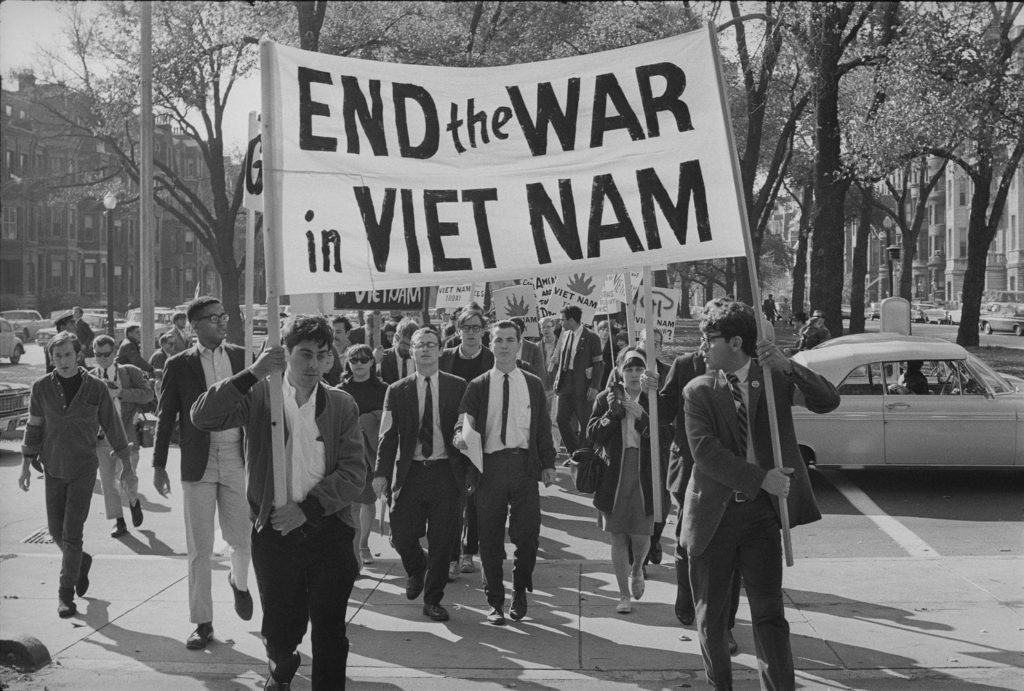

Here’s Juri on the idiocy of using other people’s countries to fight our wars and believing that we can ever win hearts and minds that way: “I had no resentments against the kids at all with the anti-war stuff. I obviously had mixed feelings myself. I mean, I wasn’t against the war. I thought it was in the wrong place. Literally. Originally it was supposed to be in Laos. I didn’t think that was the right place. They moved it to Viet Nam, really, because of the supply problem, and the access from the sea. But nobody wanted that war to be there. I thought the time to go to war is when the North Vietnamese are landing in Los Angeles. It’s not even a joke. To go to somebody else’s country to have your war, there’s something basically stupid and wrong about this. Forget about the moral question, which is obvious. But the lack of familiarity. You are going off into a culture of which you have no knowledge. A country with 54 minority groups. All of them at each other. Plus all the competing ideologies. A complete vortex.

“The expression I’d always hear was, ‘Well, it’s much better there than here. We don’t want to do this in California. Let’s do it in Korea, let’s do it in Viet Nam.’ What kind of moral position is that, to go and blow up somebody else’s country? Once you bring in artillery and bombing, all hope of winning over a population really ends. There’s no way to control the damage from that. You are creating as much opposition as you are destroying. In fact, I would venture to say you’re probably creating more opposition. The people who survive that, whose families have suffered under the bombing or the artillery, are going to come get you. The politics don’t matter anymore. It’s simply a personal thing.

“The brilliant [North Vietnamese] General Giap had been a history professor turned general who defeated the French. I don’t know how much he’s driven by ideology or by the memory of his beloved dying in a French prison. On the Southern side it was equally bad. Diem had lost his oldest brother and the oldest brother’s son to the Communists, who executed the father and the son by burying them alive. That kind of thing digs much deeper than any ideology. Once the bombs drop and the flesh is rent, no concept is going to hold back the animosity or the opposition of a people.”