I recently had the pleasure of being interviewed by fellow veteran Tom Glenn for the Washington Independent Review of Books. Glenn’s review of Red Flags is here.

I recently had the pleasure of being interviewed by fellow veteran Tom Glenn for the Washington Independent Review of Books. Glenn’s review of Red Flags is here.

What prompted you to write Red Flags now, more than forty years after your deployment to Vietnam?

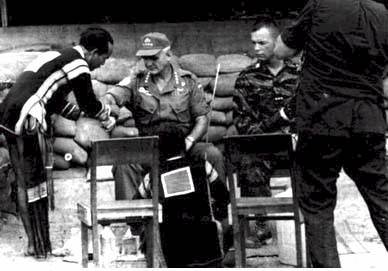

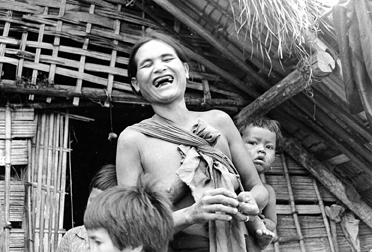

No one had yet written about our running battle with the South Vietnamese, our hosts at the war we were paying to attend. I wanted to get into their elaborate, even treasonous corruption and our complicity in it. The Vietnamese were diverting our supplies – medicines, gasoline, ammunition, weapons, rations — to the black market and on to the enemy, and we looked away. They also avoided engaging the North Vietnamese invading their territory, and left it to their civilian village militias and our forces to bear the brunt of stopping them. Finally, I felt I owed it to the Montagnard tribes people to describe their mistreatment at the hands of the Vietnamese, persecution that got so bad it led to violent mutinies, which in turn caused terrible conflicts for their American advisers who actually felt a greater loyalty to the aboriginal tribes than to Saigon.

What parallels do you see between Vietnam and Afghanistan?

A lot. I can’t believe the US Agency for International Development (USAID) is back at it again, trying to win hearts and minds with paved roads and concrete wells. It’s all too familiar. A sanctuary for the enemy just across the porous border of Pakistan. The corruption – all the way up to family members of the heads of state, the missing millions, warlords with private armies, a besieged government out of favor with Washington, fixed elections, institutionalized heroin trafficking, and another undeclared war against insurgents. How we were inveigled into it also bears an uncanny similarity. Like Kabul, the black-market and aid-corrupted government in Saigon was mainly focused on a) self perpetuation, b) diverting economic and military aid for personal profit, c) the transshipment of illegal drugs, using their military aircraft to haul most of it, and d) oh, yeah – doing just enough about the insurgents to placate the Americans so the cornucopia would stay open for business. Reading about police and Afghan military turning on their American instructors and actually killing them is also alarmingly familiar. As are the recent stories of failed Afghan safe-haven villages (called “strategic hamlets in Vietnam) where our civic assistance has neglected to provide the inhabitants with so much as water.

In the last year, the stream of new books about Vietnam has grown. What are your thoughts on why?

I think the interest is spurred by the constant press references to the similarities with our earliest counter-insurgency war in Southeast Asia. Recently declassified material is also fueling it; many documents are finally seeing daylight. I mean, did you know the first Westerners to covertly attack North Vietnamese territory during the war were Norwegian contractors? Also, we finally seem open to hearing from our former enemies. L. Borton, for instance, has translated a fascinating memoir, due out next year from Persea Books, by a North Vietnamese combat doctor in the highlands. No polemics, just what happened.

For the vets, there is probably an emotional corollary to this uptick in books. My Army friend Harry Pewterbaugh says that guys—like five of us who had served together — started looking for one another as we hit our 60s. There’s a spike on Internet vet forums of old friends looking for each other.

The fiction craftsmanship in Red Flags is exemplary, but your career has been in publishing. Where and how did you master the craft?

I’ve spent my adult life working with writers. My late wife, Laurie Colwin, was an accomplished writer and our daughter is showing signs of carrying her genes. I’ve been around it forever as an editor, mostly working on fixing whatever was ailing an author’s book. I harbored the ambition but had little time to devote to it. The first one took forever as a result. And Red Flags wasn’t so swiftly done either. I obsess about getting the details as right as possible and it slows me down.

Red Flags is beautifully organized, paced, and written. How long did the book take you? How many drafts did you do?

From final first draft to the final-final-draft took two years, but I’d been working on the book for two years before that. Number of drafts? I’ haven’t counted them up but the forests of North America stand grateful for my computer. Certainly another whole book’s worth of text landed on the cutting-room floor.

You and I were in the highlands at the same time (1967-1968), but our paths never crossed. Did you foresee then how the war was going to end?

I moved around three provinces and passed through all the major coastal bases, so we might have bumped into one another.

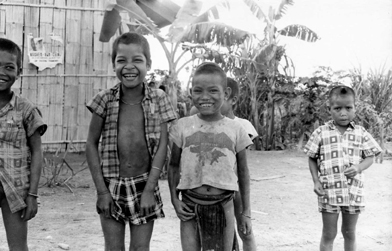

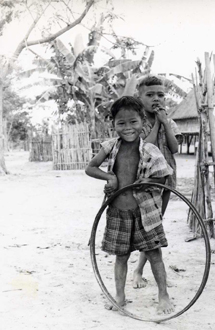

Did I see the inevitable end coming? Yes. We had the planes, tanks and technology. But they had General Giap and the ingenious strategies. The American command kept trying to taunt, lure, trap the North Vietnamese forces into big unit battles but rarely succeeded. The NVA didn’t cooperate. Even when we did manage to interest the VC in this sort of combat, the outcome seemed not to matter. The Vietnamese people didn’t care. They just wanted it to stop. Especially the bombing and the artillery. Their government never came up with some ideal to rally around, as had the North. Forget communism. The rallying cry was independence, a unified country free of foreigners. Ho’s Viet Minh fought the Japanese. Giap flat out defeated the French, and Hanoi promised to wait out the Americans indefinitely. We didn’t often lose battles (assaults really– nothing was ever held) but we absolutely didn’t win the revolution.

I’ve known for a long time about what I call “Vietnam Addiction”—so many of us couldn’t get enough of Vietnam despite the horrors of the war. Your character Miser seems to suffer from the malady. Did you know people who were Vietnam-addicted?

Lots. We teased our “Miser” by running him for mayor of the local town. There were non-coms like him who’d been in Vietnam for seven or eight years, and rarely came closer to the U.S. mainland than Hawaii. They were like centurions who had soldiered around the Asian rim for too long. They were more at home there than in their own culture. They’re still out there too, doing security work in exotic places for three hundred a day, running bars in Bangkok, or living quietly in retirement in South Korea.

Many black noncoms stayed because there were no impediments to making rank in a combat zone, as opposed to serving stateside or in garrisons in Europe. Their courage was recognized and rewarded promptly, especially by those whose asses they saved. Their experience was needed and respected. Even so, it wasn’t always enough to get them into the mostly white elite outfits like Special Forces.

The seriously addicted ones were the guys who liked bearing arms, liked the actual weapons, the responsibility and the power, the life-and-death risk- taking. Everyone who has ever sighted a weapon for real has felt that kick but it dissipates mighty fast for most of us. For a few the thrill never lessened.

For ordinary mortals Vietnam marked us for life and draws us still.

Do you have any desire to return to Vietnam? If you went back, where would you go? Who and what would you see?

I have a Quaker friend who’s lived in Hanoi for twenty years. I’d liked to see her — and Saigon. I’d liked to see the Montagnards but I wouldn’t like to see what’s happened to them. And it’s unlikely I would be permitted to, either. The highlands were closed to foreigners after the tribes people began protesting their mistreatment. I wouldn’t want to walk around remembering.

What do you most love and regret about your Vietnam experience?

Regret? Marriage number one, I suppose, and that she didn’t write me a Dear John while I was still there (she delivered the news in person on my return). If she had, I would have stayed in Vietnam, mustered out there and maybe signed on with some news outfit as a stringer…maybe gone after an interview with Colonel Kurtz upriver. I would have loved to interview Col. George S. Patton IV, the son. What do I miss most? The guys.

You’ve now written two successful novels. What next? More novels set in Vietnam?

Maybe one more, set in 1963 in Saigon. Then one in Europe, with lots of Nazis.

What part of the Vietnam story needs more attention from writers? Put differently, what books about Vietnam would you like to see written?

Definitely the story of the Montagnards’ mutinies against the South Vietnamese in ’64 and ’65, and in the last hours of April ‘75 as South Vietnam tanked. I’d like to read about the repercussions against their Special Forces leaders who, rumor has it, were scattered afterward for fear of where their loyalties lay. Also, the story of the Special Forces’ agent who they discovered to be a double, maybe triple agent, so they got him drunk, shot him dead and threw him overboard into the South China Sea one night — which resulted in the arrest of the top Green Beret commander. No one’s ever gotten the inside story. And at least a magazine piece on the covert Norwegian contractors’ nocturnal work in the Gulf of Tonkin. Want scandal? How about the cover-up of poison gas that killed Marines at the DMZ? That one’s still deep in the vaults.

Do you still believe in war? Does it have a purpose that will ever be accomplished?

I was born in a war, grew up a homeless refugee in camps in Germany where our playgrounds were the abandoned, eroded training trenches of Hitler’s army. I was far more skeptical about Vietnam than my peers and had no illusions about warfare. Still, when I saw it up close I was dumbstruck at the audacity of the Johnson administration that they could pose on the lip of the erupting volcano that was Indochina so late in the game, and think they could will it to stop by threatening the lava with superior firepower and Lend-Lease aid. Utter hubris. The one good thing the fall of Vietnam might do, I thought, was discredit such thinking.

Our kids may grow up on video war games but the first military academy in Vietnam was already up and running at the time of Christ. I never thought we would again dare lecture ancient peoples about waging war, certainly not folks whose boys receive AK-47s as birthday presents.

Does it surprise you that such an enlightened species still resorts to violence?

Somewhat. The Canadians get it. The Germans and Japanese have learned, albeit the hard way. Why can’t we? But then we don’t know the violence we are suborning. If a photographer covering the Middle East takes truly unnerving photos or pictures of American dead, he’s tossed from the theater. So he doesn’t. Network TV footage versus Al Jazeera’s? – no comparison. If you’d seen Japanese photographs from the Vietnam War, you would think the images from the My Lai massacre were greeting cards. Recently a seventy-dollar medical book on the military’s radical new trauma surgeries was nearly censored lest the public see them. We are insulated. Nor do we have any real sense of being in a state of war — because we’re not. “The army is at war,” says historian David M. Kennedy. “We have managed to create and field an armed forces that can engage in very, very lethal warfare without the society in whose name it fights breaking a sweat.” Which is why – God help me – we need the Draft back. We would’ve been out of there nine-and-a-half years ago.

What surprises me more is that an enlightened country sends an army thousands of miles after terrorists who’ve attacked New York and Washington and later tried for other domestic targets. I would have expected we install real airport security, radiation detectors in our ports, secure our reservoirs, power plants, nuclear reactors, trains and mass transit, and distribute anthrax antidote doses to every citizen in the country — as Homeland Security started to do but was stopped because it would constitute illegal distribution of a prescription drug. Go figure. I still don’t understand how putting a conventional army there would stop unconventional attacks here. Is any train safe in this country? Apparently a question Bin Laden and his friends were contemplating too before his untimely death. You think our trains are safe now that he’s eliminated.

What would literature be without the literature of war?

Funny. Uplifting. Real. Most war literature is a kind of pornography. Dick Lit. It is to war what a Playboy foldout is to an actual woman. Someone asked me what it was really like guarding a perimeter at night. You can imagine what it would be in a movie or novel. I told him to go home, take his lawn ornament into his bathroom, step in the tub with it, have his wife douse the lights and close the door. Then turn on the shower and stand there for two hours holding the fourteen pounds of dwarf.