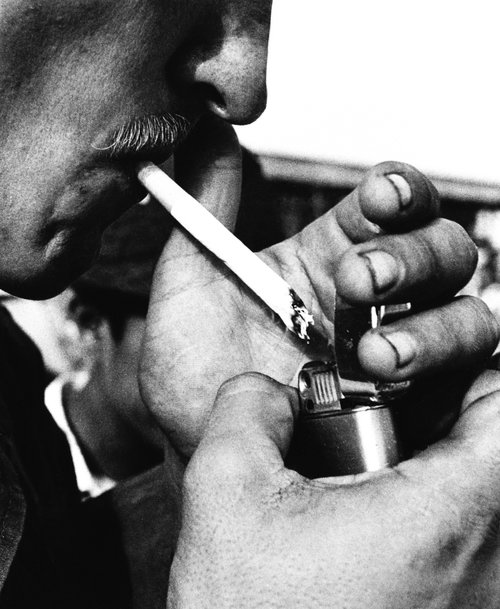

One of the many ways the tiny outpost where Juris served was unlike the rest of Viet Nam was the lack of a certain type of organized commercial venture: “The Vietnamese were just as entrepreneurial as in the big cities, but some of the universal signals were not there. You could go to the perimeter of any major base and slap yourself in the chest with a twig and some vendor would pop up offering you dope of some variety, either bags of marijuana or perfectly rolled marijuana cigarettes, in the carton, perfectly sealed as though it had never been opened. I think they were called Buddhas or some slang reference like that. In Cheo Reo, even that signal wasn’t there. On occasion we were visited by large units of Americans who were slapping themselves silly at the perimeter wondering where the hell were the vendors?”